IELTS Listening The hunt for sunken settlements and ancient shipwrecks listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the History / Academic lecture subject.

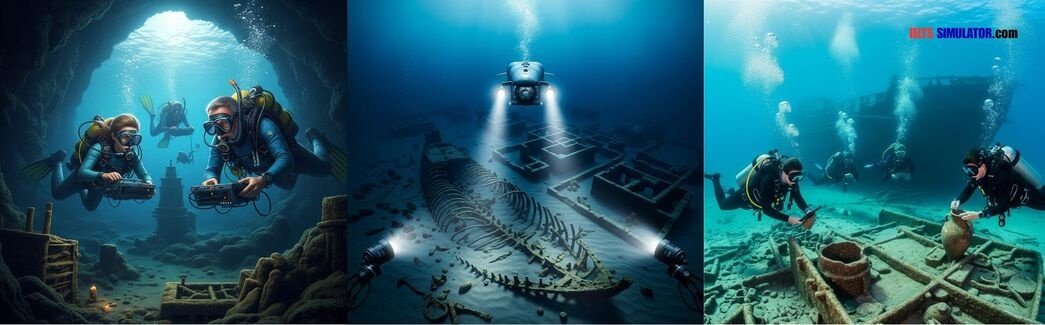

Archaeology: In today’s class, I’m going to talk about marine Archaeology, the branch of archaeology focusing on human interaction with sea lakes and rivers. It’s the study of ships, cargoes, and shipping facilities on other physical remains. I’ll give you an example. Then go on to show how this type of research is being transformed by the use of the latest technology.

🎧Attempt Free Listening Test…

At least jam was a village on the coast of the eastern Mediterranean, which seems to have been thriving until around seven thousand BC. The residents kept cattle, caught fish and stored grain. They had wells for fresh water. Many of their houses were built around a courtyard and were constructed of stone. The village contained an impressive monument. Seven half-tonne stones standing in a semi-circle around the Q31 spring that might have been used for ceremonial purposes at Lidiane may have been destroyed swiftly by a tsunami

or climate change may have caused glasses to melt on ancient sea levels to rise, flooding the village gradually. Whatever the cause, it now lies ten metres below the surface of the Mediterranean, buried under sand at the bottom of the sea. It’s being described as the largest and best-preserved prehistoric settlement ever found on the seabed. For marine archaeologists, Atlit Yam is a treasure trove.

Research on the building’s Q32 tools and the human remains has revealed how the bustling village once functioned and even what diseases some of its residents suffered from. But of course, this is only one small village, one window into a lost world. For a fuller picture, researchers need more sunken settlements, but the hard part is finding them. Underwater research used to require divers to find shipwrecks or artefacts. But in the second half of the twentieth century, various types of underwater vehicles were developed, some ancient controlled from a ship on the surface and some of them autonomous, which means they don’t need to be operated by a person, autonomous underwater vehicles or AUVs. These are used in the oil industry, for instance, to create Q33 maps of the sea bed before rigs and pipelines are installed

to navigate. They use senses such as compasses. And so no. Until relatively recently they were very expensive and so Q34 heavy that they had to be launched from a large vessel with a winch. But the latest AUVs, are much easier to manoeuvre.

They could be launched from the shore or a small ship, and they’re much cheaper, which makes them more ancient and accessible to research teams. They’re also very sophisticated. They can communicate with each other on DH, for example, work out the most efficient way to survey a site or to find a particular object on the sea bed

field tests show the approach can work. For example, in a trial in twenty fifteen three, a UV has searched for Rex but Marty Mummy, off the coast of Sicily.

The site is the final resting place of an ancient Roman ship, which sank in the sixth century While ferrying prefabricated Q35 marble elements for the construction of an early church, the AUVs mapped the area in detail, finding other ships carrying columns of the same material.

Creating an Internet in the sea for a U visa to communicate is no easy matter. Wi-fi networks on land use electromagnetic waves, but in water, these will only travel a few centimetres. Instead, a more complex mix of technologies is required for short distances. They share data using Q36 light, while acoustic waves were used to communicate over long distances. But more creative solutions are also being developed, where an AUV working on the seabed offloads data to a second AUV, which then surfaces on beams the data home to the research team using a satellite.

There’s also a system that enables AUVs to share information from seabed scans and other data. So even a UV surveying the seabed finds an intriguing object. It can share the coordinates of the object that is, its position with a nearby, AUV that carries superior Q37 cameras. And arrange for that a UV to make a closer inspection of the object.

Marine archaeologists are excited about the huge potential of these AUVs for their discipline. One site where they’re going to be deployed is the Gulf of Barati off the Italian coast in nineteen seventy for a two-thousand-year-old Roman vessel was discovered here in eighteen metres of water when it sank. It was carrying Q38 medical goods in wooden or tin receptacles.

Its cargo gives us insight into the treatments available all those years ago, including tablets that are thought to have been dissolved to form a cleansing liquid for the Q39 eyes Other Roman ships went down nearby by taking their cargoes with um, some held huge pots made of terra cotta. Some were used for transporting cargoes of olive oil. The others held Q40 wine. In many cases, it’s only these containers that remain, while the wooden ships have been buried under silt on the seabed.

🎧Attempt Free Listening Test…

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009