IELTS READING – Early Childhood Education S31AT1

| IELTS Reading Early Childhood Education reading practice test has 10 questions belongs to 🎓 Education & Child Development subject.. |

New Zealand’s National Party spokesman on education, Dr Lockwood Smith, recently visited the US and Britain. Here he reports on the findings of his trip and what they could mean for New Zealand’s education policy

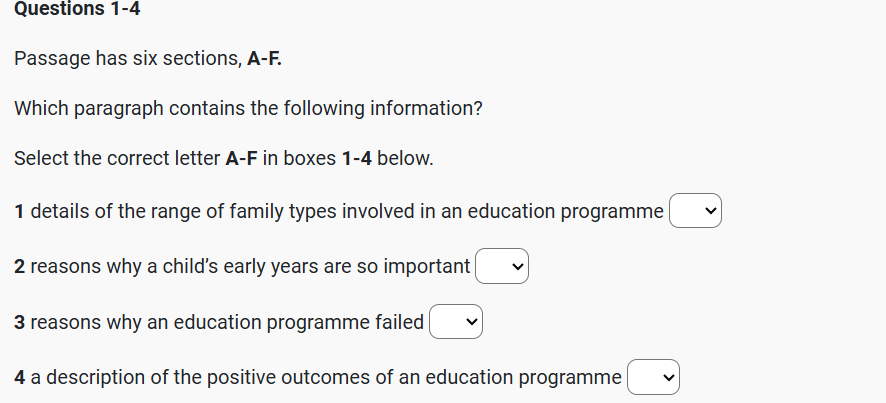

A. ’Education To Be More’ was published last August. It was the report of the New Zealand Government’s Early Childhood Care and Education Working Group. The report argued for enhanced equity of access and better funding for childcare and early childhood education institutions. Unquestionably, that’s a real need; but since parents don’t normally send children to pre-schools until the age of three, are we missing out on the most important years of all?

B. A 13 year study of early childhood development at Harvard University has shown that, by the age of three, most children have the potential to understand about 1000 words – most of the language they will use in ordinary conversation for the rest of their lives.

Furthermore, Q2 research has shown that while every child is born with a natural curiosity, if can be suppressed dramatically during the second and third years of life. Researchers claim that the human personality is formed during the first two years of life, and during the first three years children learn the basic skills they will use in all their later learning both at home and at school. Once over the age of three, children continue to expand on existing knowledge of the world.

C. It is generally acknowledged that young people from poorer socio-economic backgrounds fend to do less well in our education system. That’s observed not just in New Zealand, but also in Australia, Britain and America. Q10 In an attempt to overcome that educational under-achievement, a nationwide programme called ‘Headstart’ was launched in the United States in 1965. Q9 A lot of money was poured into it. It took children into pre-school institutions at the age of three and was supposed to help the children of poorer families succeed in school.

Q7 Despite substantial funding, Q3 results have been disappointing. It is thought that there are two explanations for this. First, the programme began too late. Many children who entered it at the age of three were already behind their peers in language and measurable intelligence. Second, the parents were not involved. At the end of each day, ‘‘ Q6 children returned to the same disadvantaged home environment.

D. As a result of the growing research evidence of the importance of the first three years of a child’s life and the disappointing results from ‘Headstart’, a pilot programme was launched in Missouri in the US that focused on parents as the child’s first teachers. The ‘Missouri’ programme was predicated on research showing that working with the family, rather than bypassing the parents, is the most effective way of helping children get off to the best possible start in life. Q1 The four-year pilot study included 380 families who were about to have their first child and who represented a cross-section of socio-economic status, age and family configurations. Q5 They included single-parent and two-parent families, families in which both parents worked, and families with either the mother or father at home.

Q8 The programme involved trained parent-educators visiting the parents’ home and working with tire parent, or parents, and the child. Information on child development, and guidance on things to look for and expect as the child grows were provided, plus guidance in fostering the child’s intellectual, language, social and motor-skill development. Periodic check-ups of the child’s educational and sensory development (hearing and vision) were made to detect possible handicaps that interfere with growth and development. Medical problems were referred to professionals.

Parent educators made personal visits to homes and monthly group meetings were held with other new parents to share experience and discuss topics of interest. Parent resource centres, located in school buildings, offered learning materials for families and facilitators for child core.

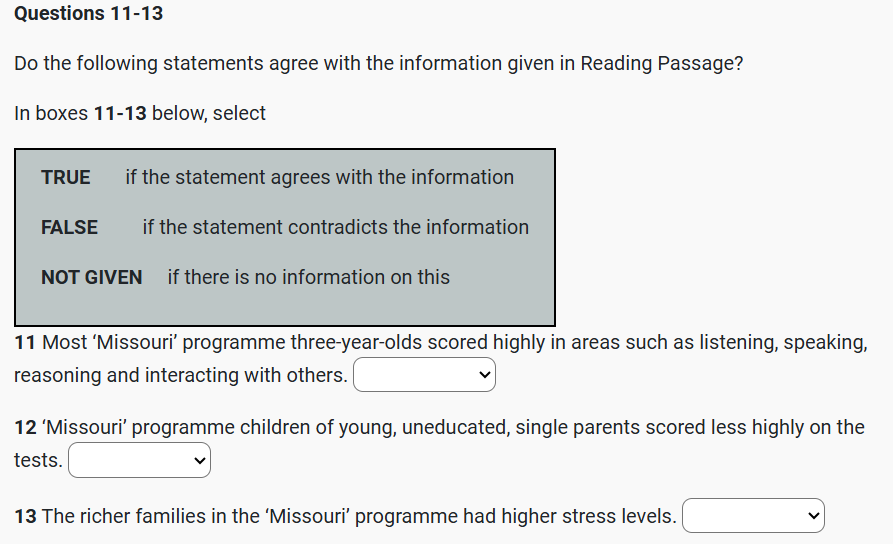

E. At the age of three, the children who had been involved in the ‘Missouri’ programme were evaluated alongside a cross-section of children selected from the same range of socio-economic backgrounds and family situations, and also a random sample of children that age. Q4 The results were phenomenal. By the age of three, the children in the programme were significantly more advanced in language development than their peers, had made greater strides in problem-solving and other intellectual skills, and were further along in social development, in fact, Q11 the average child on the programme was performing at the level of the top 15 to 20 per cent of their peers in such things as auditory comprehension, verbal ability and language ability.

Most important of all, the traditional measures of ‘risk’, such as parents’ age and education, or whether they were a single parent, bore little or no relationship to the measures of achievement and language development. Q12 Children in the programme performed equally well regardless of socio-economic disadvantages. Child abuse was virtually eliminated. The one factor that was found to affect the child’s development was family stress leading to a poor quality of parent-child interaction. That interaction was not necessarily bad in poorer families.

F. These research findings are exciting. There is growing evidence in New Zealand that children from poorer socio-economic backgrounds are arriving at school less well-developed and that our school system tends to perpetuate that disadvantage. The initiative outlined above could break that cycle of disadvantage. The concept of working with parents in their homes, or at their place of work, contrasts quite markedly with the report of the Early Childhood Care and Education Working Group. Their focus is on getting children and mothers access to childcare and institutionalised early childhood education. Education from the age of three to five is undoubtedly vital, but without a similar focus on parent education and on the vital importance of the first three years, some evidence indicates that it will not be enough to overcome educational inequity.

Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009