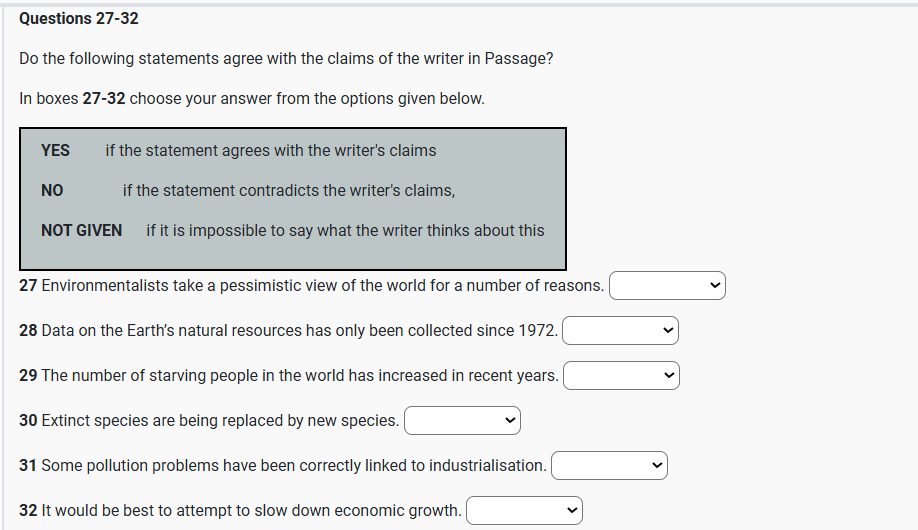

IELTS READING – BAKELITE S30AT1

| IELTS Reading BAKELITE reading practice test has 10 questions belongs to Science & Invention subject.. |

The birth of modern plastics

In 1907, Leo Hendrick Baekeland, a Belgian scientist working in New York, discovered and patented a revolutionary new synthetic material. His invention, which he named ‘Bakelite’, was of enormous technological importance, and effectively launched the modern plastics industry.

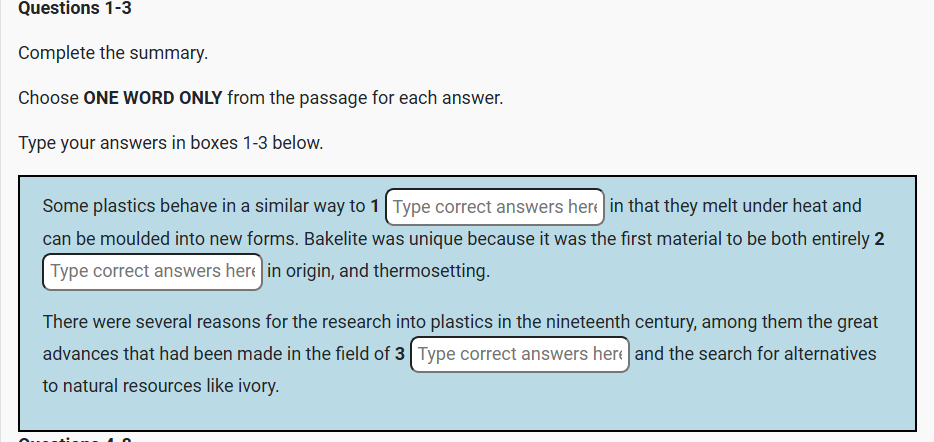

The term ‘plastic’ comes from the Greek plassein, meaning ‘to mould’ Some plastics are derived from natural sources, some are semi-synthetic (the result of chemical action on a natural substance), and some are entirely synthetic, that is, chemically engineered from the constituents of coal or oil. Some are ‘thermoplastic’, which means that, like Q1 candlewax, they melt when heated and can then be reshaped. Others are ‘thermosetting’: like eggs, they cannot revert to their original viscous state, and their shape is thus fixed forever Bakelite had the distinction of being the first totally Q2 synthetic thermosetting plastic.

The history of today’s plastics begins with the discovery of a series of semi-synthetic thermoplastic materials in the mid-nineteenth century. The impetus behind the development of these early plastics was generated by a number of factors – immense technological progress in the domain of Q3 chemistry, coupled with wider cultural changes, and the pragmatic need to find acceptable substitutes for dwindling supplies of ‘luxury’ materials such as tortoiseshell and ivory.

Baekeland’s interest in plastics began in 1885 when, as a young chemistry student in Belgium, he embarked on research into phenolic resins, the group of sticky substances produced when phenol (carbolic acid) combines with an aldehyde (a volatile fluid similar to alcohol). He soon abandoned the subject, however, only returning to it some years later. By 1905 he was a wealthy New Yorker, having recently made his fortune with the invention of a new photographic paper. While Baekeland had been busily amassing dollars, some advances had been made in the development of plastics. The years 1899 and 1900 had seen the patenting of the first semi-synthetic thermosetting material that could be manufactured on an industrial scale. In purely scientific terms, Baekeland’s major contribution to the field is not so much the actual discovery of the material to which he gave his name, but rather the method by which a reaction between phenol and formaldehyde could be controlled, thus making possible its preparation on a commercial basis. Q11 On 13 July 1907, Baekeland took out his famous patent describing this preparation, the essential features of which are still in use today.

The original patent outlined a three-stage process, in which phenol and formaldehyde (from wood or coal) were initially combined under vacuum inside a large egg-shaped kettle. The result was a resin known as Novalak, which became soluble and malleable when heated. The resin was allowed to cool in shallow trays until it hardened, and then broken up and ground into powder. Other substances were then introduced: including Q5 fillers, such as woodflour, asbestos or cotton, which increase strength and moisture resistance, catalysts (substances to speed up the reaction between two chemicals without joining to either) and hexa, a compound of ammonia and formaldehyde which supplied the additional formaldehyde necessary to form a thermosetting resin. This resin was then left to cool and harden, and ground up a second time. The resulting granular powder was Q7 raw Bakelite, ready to be made into a vast range of manufactured objects. In the last stage, the heated Bakelite was poured into a hollow mould of the required shape and subjected to extreme heat and Q8 pressure, thereby ‘setting’ its form for life.

The design of Bakelite objects, everything from earrings to television sets, was governed to a large extent by the technical Q9 requirements of the moulding process. The object could not be designed so that it was locked into the mould and therefore difficult to extract. A common general rule was that objects should taper towards the deepest part of the mould, and Q10 if necessary the product was moulded in separate pieces. Moulds had to be carefully designed so that the molten Bakelite would flow evenly and completely into the mould. Sharp corners proved impractical and were thus avoided, giving rise to the smooth, ‘streamlined’ style popular in the 1930s. The thickness of the walls of the mould was also crucial’ thick walls took longer to cool and harden, a factor which had to be considered by the designer in order to make the most efficient use of machines.

Q12 Baekeland’s invention, although treated with disdain in its early years, went on to enjoy an unparalleled popularity which lasted throughout the first half of the twentieth century. It became the wonder product of the new world of industrial expansion – ‘the material of a thousand uses’. Being both non-porous and heat-resistant, Bakelite kitchen goods were promoted as being germ-free and sterilisable. Electrical manufacturers seized on its insulating properties, and consumers everywhere relished its Q13 dazzling array of shades, delighted that they were now, at last, no longer restricted to the wood tones and drab browns of the pre-plastic era. It then fell from favour again during the 1950s and was despised and destroyed in vast quantities. Recently, however, it has been experiencing something of a renaissance, with renewed demand for original Bakelite objects in the collectors’ marketplace, and museums, societies and dedicated individuals once again appreciating the style and originality of this innovative material.

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com