IELTS READING – Back to the future of skyscraper design S19AT2

IELTS READING Back to the future of skyscraper design reading practice test has 10 questions belongs to Environmental Design & Engineering subject..

Answers to the problem of excessive electricity use by skyscrapers and large public buildings can be found in ingenious but forgotten architectural designs of the 19th and early 20th centuries

A. The Recovery of Natural Environments in Architecture by Professor Alan Short is the culmination of 30 years of research and award-

winning green building design by Short and colleagues in Architecture, Engineering, Applied Maths and Earth Sciences at the University of Cambridge. The crisis in building design is already here,’ said Short. ‘Policy makers think you can solve energy and building problems with gadgets. You can’t. As global temperatures continue to rise, we are going to continue to squander more and more energy on keeping our buildings mechanically cool until we have run out of capacity.’

B. Short is calling for a sweeping reinvention of how skyscrapers and major public buildings are designed – to end the reliance on sealed buildings which exist solely via the ‘life support’ system of vast air conditioning units. Instead, he shows it is entirely possible to accommodate natural ventilation and cooling in large buildings by looking into the past, Q18 before the widespread introduction of air conditioning systems, which were ‘relentlessly and aggressively marketed’ by their inventors.

C. Short points out that to make most contemporary buildings habitable, they have to be sealed and air-conditioned. The energy use and carbon emissions this generates is spectacular and largely unnecessary. Buildings in the West account for 40-50% of electricity usage, generating substantial carbon emissions, and the rest of the world is catching up at a frightening rate. Q15 Short regards glass, steel and air-conditioned skyscrapers as symbols of status, rather than practical ways of meeting our requirements.

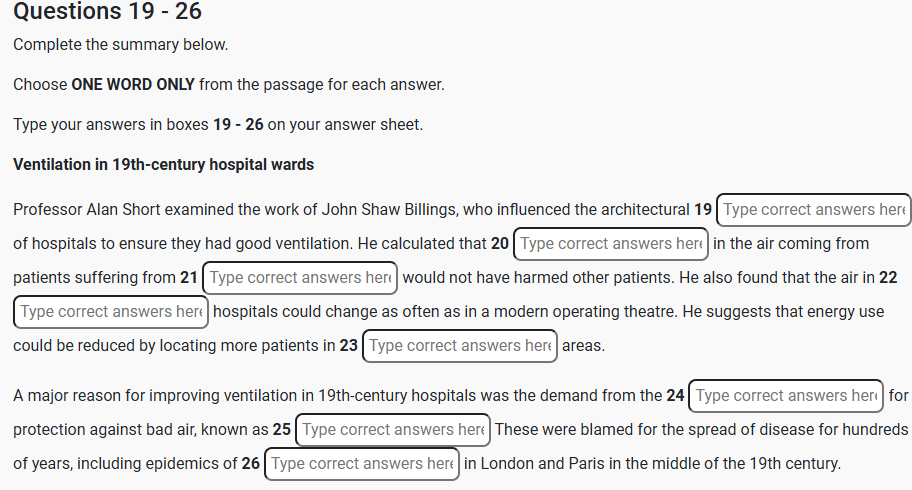

D. Short’s book highlights a developing and sophisticated art and science of ventilating buildings through the 19th and earlier-20th centuries, including the design of ingeniously ventilated hospitals. Of particular interest were those built to the Q19 designs of John Shaw Billings, including the first Johns Hopkins Hospital in the US city of Baltimore (1873-1889). Q17 ‘We spent three years digitally modelling Billings’ final designs,’ says Short. ‘We put Q20 pathogens in the airstreams, modelled for someone with Q21 tuberculosis (TB) coughing in the wards and we found the ventilation systems in the room would have kept other patients safe from harm.

E. Q16 ’We discovered that 19th-century hospital Q22 wards could generate up to 24 air changes an hour – that’s similar to the performance of a modern-day, computer-controlled operating theatre. We believe you could build wards based on these principles now. Single rooms are not appropriate for all patients. Q23 Communal wards appropriate for certain patients – older people with dementia, for example – would work just as well in today’s hospitals, at a fraction of the energy cost.’ Professor Short contends the mindset and skill-sets behind these designs have been completely lost, lamenting the disappearance of expertly designed theatres, opera houses, and other buildings where up to half the volume of the building was given over to ensuring everyone got fresh air.

F. Q14 Much of the ingenuity present in 19th-century hospital and building design was driven by a panicked Q24 public clamouring for buildings that could protect against what was thought to be the lethal threat of Q25 miasmas – toxic air that spread disease. Miasmas were feared as the principal agents of disease and epidemics for centuries, and were used to explain the spread of infection from the Middle Ages right through to the Q26 cholera outbreaks in London and Paris during the 1850s. Foul air, rather than germs, was believed to be the main driver of ‘hospital fever’, leading to disease and frequent death. The prosperous steered clear of hospitals. While miasma theory has been long since disproved, Short has for the last 30 years advocated a return to some of the building design principles produced in its wake.

G. Today, huge amounts of a building’s space and construction cost are given over to air conditioning. ‘But I have designed and built a series of buildings over the past three decades which have tried to reinvent some of these ideas and then measure what happens. To go forward into our new low-energy, low-carbon future, we would be well advised to look back at design before our high-energy, high-carbon present appeared. What is surprising is what a rich legacy we have abandoned.’

H. Successful examples of Short’s approach include the Queen’s Building at De Montfort University in Leicester. Containing as many as 2,000 staff and students, the entire building is naturally ventilated, passively cooled and naturally lit, including the two largest auditoria, each seating more than 150 people. The award-winning building uses a fraction of the electricity of comparable buildings in the UK. Short contends that glass skyscrapers in London and around the world will become a liability over the next 20 or 30 years if climate modelling predictions and energy price rises come to pass as expected.

I. He is convinced that sufficiently cooled skyscrapers using the natural environment can be produced in almost any climate. He and his team have worked on hybrid buildings in the harsh climates of Beijing and Chicago – built with natural ventilation assisted by back-up air conditioning – which, surprisingly perhaps, can be switched off more than half the time on milder days and during the spring and autumn. Short looks at how we might reimagine the cities, offices and homes of the future. Maybe it’s time we changed our outlook.

Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009