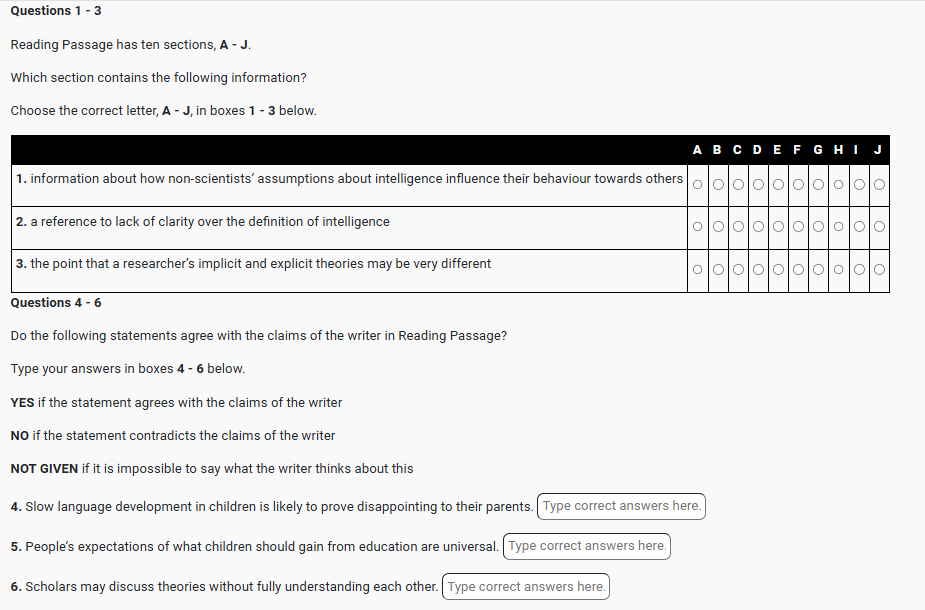

IELTS READING – The concept of intelligence S20AT1

| IELTS Reading The concept of intelligence reading practice test has 10 questions belongs to 🧠 Education & Psychology subjects.. |

A. Looked at in one way, everyone knows what intelligence is looked at in another way, no one does. In other words, people all have unconscious notions – known as ‘implicit theories’ – of intelligence, but Q2 no one knows for certain what it actually is. This chapter addresses how people conceptualize intelligence,

whatever it may actually be. But why should we even care what people think intelligence is, as opposed only to valuing whatever it actually is? There are at least four reasons people’s conceptions of intelligence matter.

B. First, implicit theories of intelligence drive the way in which people perceive and evaluate their own intelligence and that of others. To better understand the judgments people make about their own and others’ abilities, it is useful to learn about people’s implicit theories. Q4 Q1 For example, parents’ implicit theories of their children’s language development will determine at what ages they will be willing to make various corrections in their children’s speech. More generally, parents’ implicit theories of intelligence will determine at what ages they believe their children are ready to perform various cognitive tasks. Job interviewers will make hiring decisions on the basis of their implicit theories of intelligence. People will decide who to be friends with on the basis of such theories. In sum, knowledge about implicit theories of intelligence is important because this knowledge is so often used by people to make judgments in the course of their everyday lives.

C. Second, the implicit theories of scientific investigators ultimately give rise to their explicit theories. Thus it is useful to find out what these implicit theories are. Implicit theories provide a framework that is useful in defining the general scope of a phenomenon – especially a not-well-understood phenomenon. These implicit theories can suggest what aspects of the phenomenon have been more or less attended to in previous investigations.

D. Third, Q3 implicit theories can be useful when an investigator suspects that existing explicit theories are wrong or misleading. If an investigation of implicit theories reveals little correspondence between the extant implicit and explicit theories, the implicit theories may be wrong. But the possibility also needs to be taken into account that the explicit theories are wrong and in need of correction or supplementation. For example, some implicit theories of intelligence suggest the need for expansion of some of our explicit theories of the construct.

E. Finally, understanding implicit theories of intelligence can help elucidate developmental and cross-cultural differences. As mentioned earlier, Q5 people have expectations for intellectual performances that differ for children of different ages. How these expectations differ is in part a function of culture. For example, expectations for children who participate in Western-style schooling are almost certain to be different from those for children who do not participate in such schooling.

F. I have suggested that there are three major implicit theories of how intelligence relates to society as a whole (Sternberg, 1997). These might be called Hamiltonian, Jeffersonian, and Jacksonian. These views are not based strictly, but rather, loosely, on the philosophies of Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and Andrew Jackson, three great statesmen in the history of the United States.

G. The Hamiltonian view, which is similar to the Platonic view, is that Q10 people are born with different levels of intelligence and that those who are less intelligent need the good offices of the more intelligent to keep them in line, whether they are called government officials or, in Plato’s term, philosopher-kings. Herrnstein and Murray (1994) Q11 seem to have shared this belief when they wrote about the emergence of a cognitive (high-IQ) elite, which eventually would have to take responsibility Q13 for the largely irresponsible masses of non-elite (low-IQ) people who cannot take care of themselves. Left to themselves, the unintelligent would create, as they always have created, a kind of chaos.

H. Q7 The Jeffersonian view is that people should have equal opportunities, but they do not necessarily avail themselves equally of these opportunities and are not necessarily equally rewarded for their accomplishments. People are rewarded for what they accomplish if given equal opportunity. Low achievers are not rewarded to the same extent as high achievers. In the Jeffersonian view, the goal of education is not to favor or foster an elite, as in the Hamiltonian tradition, but rather Q9 to allow children the opportunities to make full use of the skills they have. My own views are similar to these (Sternberg, 1997).

I. The Jacksonian view is that all people are equal, not only as human beings but in terms of their competencies – that one person would serve as well as another in government or on a jury or in almost any position of responsibility. Q8 In this view of democracy, Q12 people are essentially intersubstitutable except for specialized skills, all of which can be learned. In this view, we do not need or want any institutions that might lead to favoring one group over another.

J. Implicit theories of intelligence and of the relationship of intelligence to society perhaps need to be considered more carefully than they have been because they often serve as underlying presuppositions for explicit theories and even experimental designs that are then taken as scientific contributions. Q6 Until scholars are able to discuss their implicit theories and thus their assumptions, they are likely to miss the point of what others are saying when discussing their explicit theories and their data.

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com