IELTS LISTENING S60T4

Time Perspective

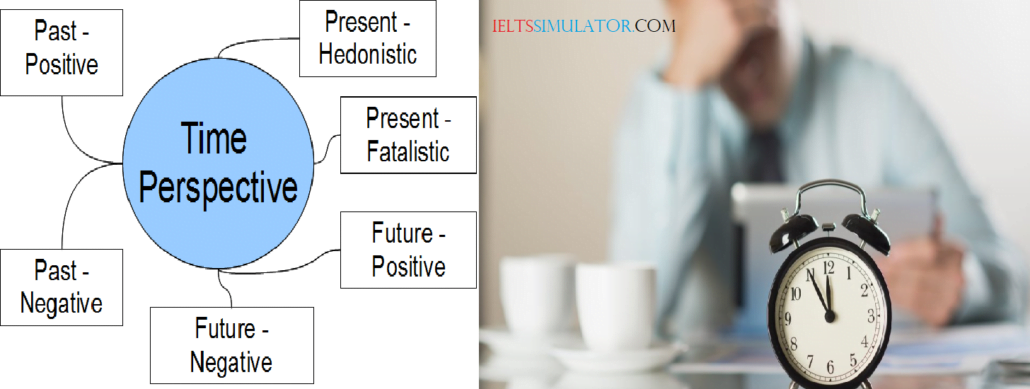

Today, I’m going to be talking about time. Specifically, I’ll be looking at how people think about time, and how these time perspectives structure our lives. According to social psychologists, there are six ways of thinking about time, which are called personal time zones.

The first two are based in the past. Past positive thinkers spend most of their time in a state of nostalgia, fondly remembering moments such as birthdays, marriages, and important achievements in their life. These are the kinds of people who keep family records, books, and photo albums. People living in the past Q31 negative time zone are also absorbed by earlier times, but they focus on all the bad things – regrets, failures, and poor decisions. They spend a lot of time thinking about how life could have been.

Attempt full listening test…

Then, we have people who live in the present. Present hedonists are driven by Q32 pleasure and immediate sensation. Their life motto is to have a good time and avoid pain. Present fatalists live in the moment too, but they believe this moment is the product of circumstances entirely beyond their control; it’s their fate. Whether it’s Q33 poverty, religion, or society itself, something stops these people from believing they can play a role in changing their outcomes in life. Life simply “is” and that’s that.

Looking at the future time zone, we can see that people classified as future Q34 active are the planners and go-getters. They work rather than play and resist temptation. Decisions are made based on potential consequences, not on the experience itself. A second future-orientated perspective, future fatalistic, is driven by the certainty of life after death and some kind of a judgement day when they will be assessed on how virtuously they have lived and what Q35 success they have had in their lives.

Okay, let’s move on. You might ask “how do these time zones affect our lives?” Well, let’s start at the beginning. Everyone is Q36 brought into this world as a present hedonist. No exceptions. Our initial needs and demands – to be warm, secure, fed, and watered – all stem from the present moment. But things change when we enter formal education – we’re taught to stop existing in the moment and to begin thinking about future outcomes.

But, did you know that every nine seconds a child in the USA drops out of school? For boys, the rate is much higher than for girls. We could easily say “Ah, well, boys just aren’t as bright as girls” but the evidence doesn’t support this. A recent study states that boys in America, by the age of twenty one, have spent 10,000 hours playing video games. The research suggests that they’ll never fit in the traditional classroom because these boys require a situation where they have the Q37 ability to manage their own learning environment.

Now, let’s look at the way we do prevention education. All prevention education is aimed at a future time zone. We say “don’t smoke or you’ll get cancer”, “get good grades or you won’t get a good job”. But with present-orientated kids that just doesn’t work. Although they understand the potentially negative consequences of their actions, they persist with the behaviour because they’re not living for the future; they’re in the moment right now. We can’t use logic and it’s no use reminding them of potential fall-out from their decisions or previous errors of judgment – we’ve got to get in their minds just as they’re about to make a choice.

Time perspectives make a big difference in how we value and use our time. When Americans are asked how busy they are, the vast majority report being Q39 busier than ever before. They admit to sacrificing their relationships, personal time, and a good night’s sleep for their success. Twenty years ago, 60% of Americans had sitdown dinners with their families, and now only 20% do. But when they’re asked what they would do with an eight-day week, they say “Oh that’d be great”. They would spend that time labouring away to achieve more. They’re constantly trying to get ahead, to get toward a future point of happiness.

So, it’s really important to be aware of how other people think about time. We tend to think: “Oh, that person’s really irresponsible” or “That guy’s power-hungry” but often what we’re looking at is not fundamental differences of personality, but really just different ways of thinking about time. Seeing these conflicts as differences in time perspective, rather than distinctions of character, can facilitate more effective cooperation between people and get the most out of each person’s individual strengths.