IELTS READING Serendipity – accidental discoveries in science Reading Practice Test has 10 Questions belong to the Science & Technology subject.. |

What do photography, dynamite, insulin and artificial sweetener have in common? Serendipity! These diverse discoveries, which have made our everyday living more convenient, were discovered partly by chance. However, Louis Pasteur noted the additional requirement involved in serendipity when he said, ‘

… chance favours only the prepared mind’.

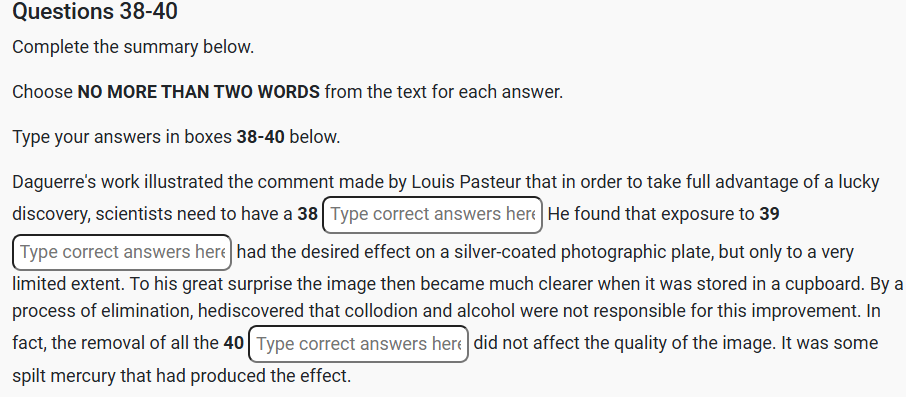

The discovery of modern photography provides an example of serendipity. In 1838, L. J. M. Daguerre was attempting to ‘fix’ images onto a copper photographic plate. After adding a silver coating to the plate and exposing it to iodine vapour, he found that the photographic image was improved but still very weak. Desperate after an investigation lasting several months, Daguerre placed a lightly exposed photographic plate in the cupboard in which laboratory chemicals such as alcohol and collodion were stored. To his amazement, when he removed the plate several days later, Daguerre found a strong image on its surface.

This image had been created by chance. It was at this point that Louis Pasteur’s ‘additional requirement’ came into play: Daguerre’s training told him that one or more of the chemicals in the cupboard was responsible for intensifying the image. After a break of two weeks, Daguerre systematically placed new photographic plates in the cupboard, removing one chemical each day. Unpredictably, good photographic images were created even after all chemicals had been removed. Daguerre then noticed that some mercury had spilled onto the cupboard shelf, and he concluded that the mercury vapour must have improved the photographic result. From this discovery came the universal adoption of the silver-mercury process to develop photographs.

Daguerre’s serendipitous research effort was rewarded, a year later, with a medal conferred by the French government. Many great scientists have benefited from serendipity, including Nobel Prize winners. In fact the scientist who established the Nobel Prize was himself blessed with serendipity. In 1861, the Nobel family built a factory in Stockholm to produce nitroglycerine, a colourless and highly explosive oil that had first been prepared by an Italian chemist fifteen years earlier. Nitroglycerine was known to be volatile and unpredictable, often exploding as a result of very small knocks. But the Nobel family believed that this new explosive could solve a major problem facing the Swedish State Railways – the need to dig channels and tunnels through mountains so that the developing railway system could expand.

Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009