IELTS READING – Why companies should welcome disorder S19AT3

| IELTS Reading Why companies should welcome disorder reading practice test has 10 questions belongs to Business & Organizational Management subject.. |

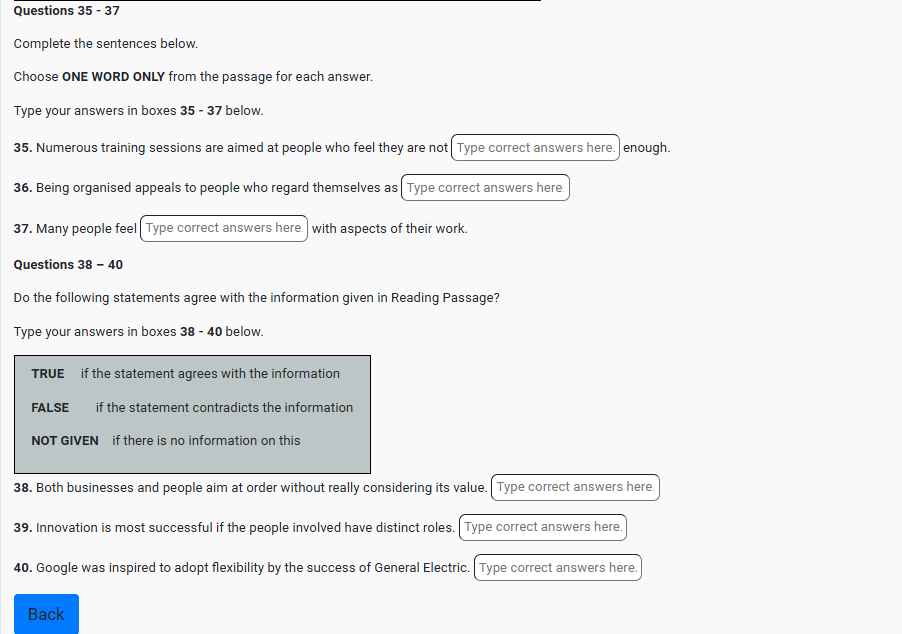

A. Organisation is big business. Whether it is of our lives – all those inboxes and calendars – or how companies are structured, a multi-billion dollar industry helps to meet this need. We have more strategies for time management,

project management and self-organisation than at any other time in human history. Q27 We are told that we ought to organise our company, our home life, our week, our day, and even our sleep, all as a means to becoming more Q35 productive. Every week, countless seminars and workshops take place around the world to tell a paying public that they ought to structure their lives in order to achieve this. This rhetoric has also crept into the thinking of business leaders and entrepreneurs, much to the delight of self-proclaimed Q36 perfectionists with the need to get everything right. The number of business schools and graduates has massively increased over the past 50 years, essentially teaching people how to organise well.

B. Q28 Ironically, however, the number of businesses that fail has also steadily increased. Work-related stress has increased. A large proportion of workers from all demographics claim to be Q37 dissatisfied with the way their work is structured and the way they are managed. This begs the question: what has gone wrong? Why is it that on paper the drive for organisation seems a sure shot for increasing productivity, but in reality falls well short of what is expected?

C. This has been a problem for a while now. Frederick Taylor was one of the forefathers of scientific management. Q29 Writing in the first half of the 20th century, he designed a number of principles to improve the efficiency of the work process, which have since become widespread in modern companies. So the approach has been around for a while.

D. Q30 New research suggests that this obsession with efficiency is misguided. The problem is not necessarily the management theories or strategies we use to organise our work; it’s the basic assumptions we hold in approaching how we work. Here it’s the assumption that order is a necessary condition for productivity. This assumption has also fostered the idea that disorder must be detrimental to organisational productivity. Q38 The result is that businesses and people spend time and money organising themselves for the sake of organising, rather than actually looking at the end goal and usefulness of such an effort.

E. Q31 What’s more, recent studies show that order actually has diminishing returns. Order does increase productivity to a certain extent, but eventually the usefulness of the process of organisation, and the benefit it yields, reduce until the point where any further increase in order reduces productivity. Some argue that in a business, if the cost of formally structuring something outweighs the benefit of doing it, then that thing ought not to be formally structured. Instead, the resources involved can be better used elsewhere.

F. Q39 In fact, research shows that, when innovating, the best approach is to create an environment devoid of structure and hierarchy and enable everyone involved to engage as one organic group. Q32 These environments can lead to new solutions that, under conventionally structured environments (filled with bottlenecks in terms of information flow, power structures, rules, and routines) would never be reached.

G. In recent times companies have slowly started to embrace this disorganisation. Many of them embrace it in terms of perception (embracing the idea of disorder, as opposed to fearing it) and in terms of process (putting mechanisms in place to reduce structure). For example, Q33 Oticon, a large Danish manufacturer of hearing aids, used what it called a ‘spaghetti’ structure in order to reduce the organisation’s rigid hierarchies. This involved scrapping formal job titles and giving staff huge amounts of ownership over their own time and projects. This approach proved to be highly successful initially, with clear improvements in worker productivity in all facets of the business. In similar fashion, the former chairman of General Electric embraced disorganisation, putting forward the idea of the ‘boundaryless’ organisation. Again, it involves breaking down the barriers between different parts of a company and encouraging virtual collaboration and flexible working. Q40 Google and a number of other tech companies have embraced (at least in part) these kinds of flexible structures, facilitated by technology and strong company values which glue people together.

H. A word of warning to others thinking of jumping on this bandwagon: the evidence so far suggests disorder, much like order, also seems to have diminishing utility, and can also have detrimental effects on performance if overused. Like order, disorder should be embraced only so far as it is useful. But we should not fear it – nor venerate one over the other. Q34 This research also shows that we should continually question whether or not our existing assumptions work.

Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009