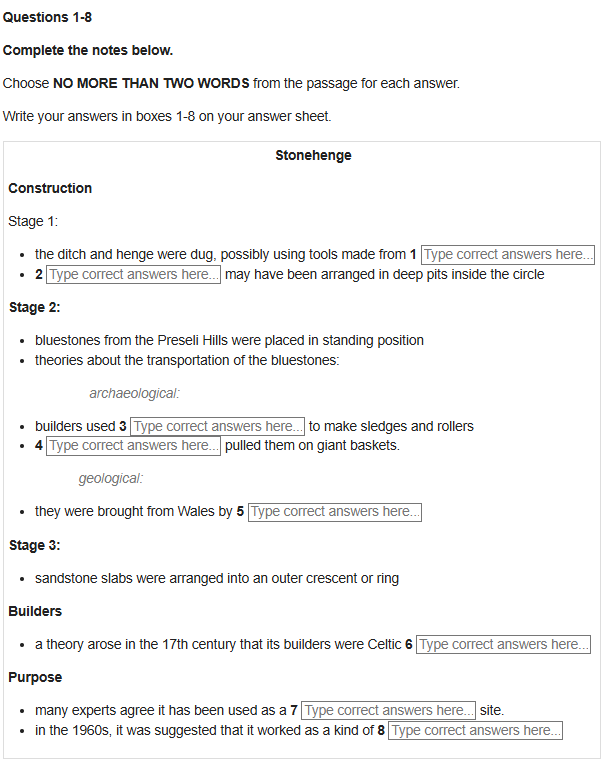

IELTS READING – Stonehenge S58AT1

| IELTS Reading Stonehenge reading practice test has 10 questions belongs to History and Archaeology subject.. |

Stonehenge

For centuries, historians and archaeologists have puzzled over the many mysteries of Stonehenge, a prehistoric monument that took an estimated 1,500 years to erect. Located on Salisbury Plain in southern England, it is comprised of roughly 100 massive upright stones placed in a circular layout.

Archaeologists believe England’s most iconic prehistoric ruin was built in several stages, ruin was with the earliest constructed 5,000 or more years ago. First, Neolithic Britons used primitive tools, which may have been fashioned out of deer antlers, to dig a massive circular ditch and bank, or henge. Deep pits dating back to that era and located within the circle may have once held a ring of timber posts, according to some scholars.

Several hundred years later, it is thought, Stonehenge’s builders hoisted an estimated 80 bluestones, 43 of which remain today, into standing positions and placed them in either a horseshoe or circular formation. These stones have been traced all the way to the Preseli Hills in Wales, some 300 kilometres from Stonehenge. How, then, did prehistoric builders without sophisticated tools or engineering haul these boulders, which weigh up to four tons, over such a great distance?

According to one long-standing theory among archaeologists, Stonehenge’s builders fashioned sledges and rollers out of tree trunks to lug the bluestones from the Preseli Hills. They then transferred the boulders onto rafts and floated them first along the Welsh coast and then up the River Avon toward Salisbury Plain; alternatively, they may have towed each stone with a fleet of vessels. More recent archaeological hypotheses have them transporting the bluestones with supersized wicker baskets on a combination of ball bearings and long grooved planks, hauled by oxen.

As early as the 1970s, geologists have been adding their voices to the debate over how Stonehenge came into being. Challenging the classic image of industrious builders pushing, carting, rolling or hauling giant stones from faraway Wales, some scientists have suggested that it was glaciers, not humans, that carried the bluestones to Salisbury Plain. Most archaeologists have remained sceptical about this theory, however, wondering how the forces of nature could possibly have delivered the exact number of stones needed to complete the circle.

The third phase of construction took place around 2000 BCE. At this point, sandstone slabs – known as ‘sarsens’ – were arranged into an outer crescent or ring; some were assembled into the iconic three-pieced structures called trilithons that stand tall in the centre of Stonehenge. Some 50 of these stones are now visible on the site, which may once have contained many more. Radiocarbon dating has revealed that work continued at Stonehenge until roughly 1600 BCE, with the bluestones in particular being repositioned multiple times.

But who were the builders of Stonehenge? In the 17th century, archaeologist John Aubrey made the claim that Stonehenge was the work of druids, who had important religious, judicial and political roles in Celtic society. This theory was widely popularized by the antiquarian William Stukeley, who had unearthed primitive graves at the site. Even today, people who identify as modern druids continue to gather at Stonehenge for the summer solstice. However, in the mid-20th century, radiocarbon dating demonstrated that Stonehenge stood more than 1,000 years before the Celts inhabited the region.

Many modern historians and archaeologists now agree that several distinct tribes of people contributed to Stonehenge, each undertaking a different phase of its construction. Bones, tools and other artefacts found on the site seem to support this hypothesis. The first stage was achieved by Neolithic agrarians who were likely to have been indigenous to the British Isles. Later, it is believed, groups with advanced tools and a more communal way of life left their mark on the site. Some believe that they were immigrants from the European continent, while others maintain that they were probably native Britons, descended from the original builders.

If the facts surrounding the architects and construction of Stonehenge remain shadowy at best, the purpose of the striking monument is even more of a mystery. While there is consensus among the majority of modern scholars that Stonehenge once served the function of burial ground, they have yet to determine what other purposes it had.

In the 1960s, the astronomer Gerald Hawkins suggested that the cluster of megalithic stones operated as a form of calendar, with different points corresponding to astrological phenomena such as solstices, equinoxes and eclipses occurring at different times of the year. While his theory has received a considerable amount of attention over the decades, critics maintain that Stonehenge’s builders probably lacked the knowledge necessary to predict such events or that England’s dense cloud cover would have obscured their view of the skies.

More recently, signs of illness and injury in the human remains unearthed at Stonehenge led a group of British archaeologists to speculate that it was considered a place of healing, perhaps because bluestones were thought to have curative powers.

Best Results Easily Get Required Score.

Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009