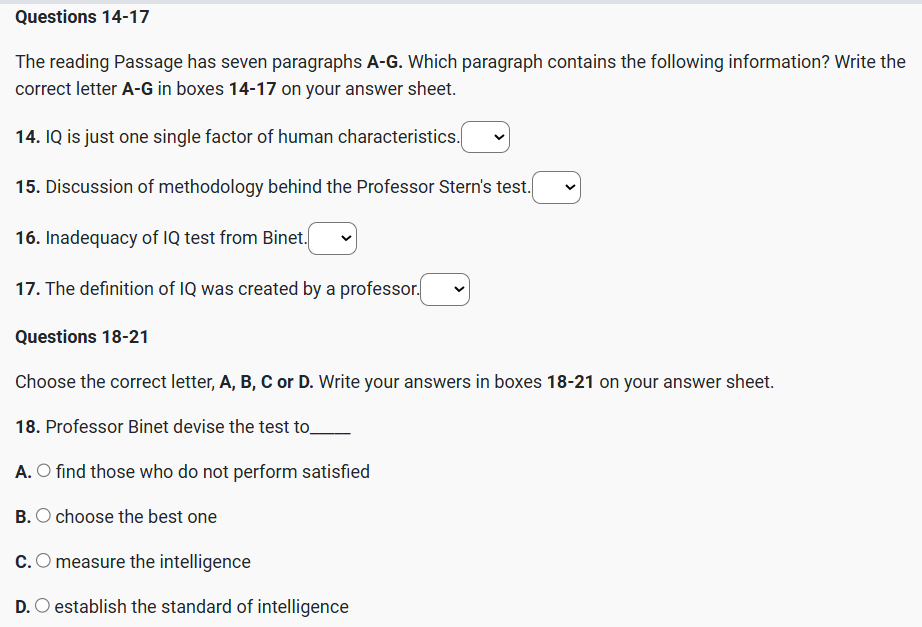

IELTS READING – Save the Turtles S54AT1

| IELTS Reading Save the Turtles reading practice test has 10 question belongs to Environment and Wildlife Conservation subject.. |

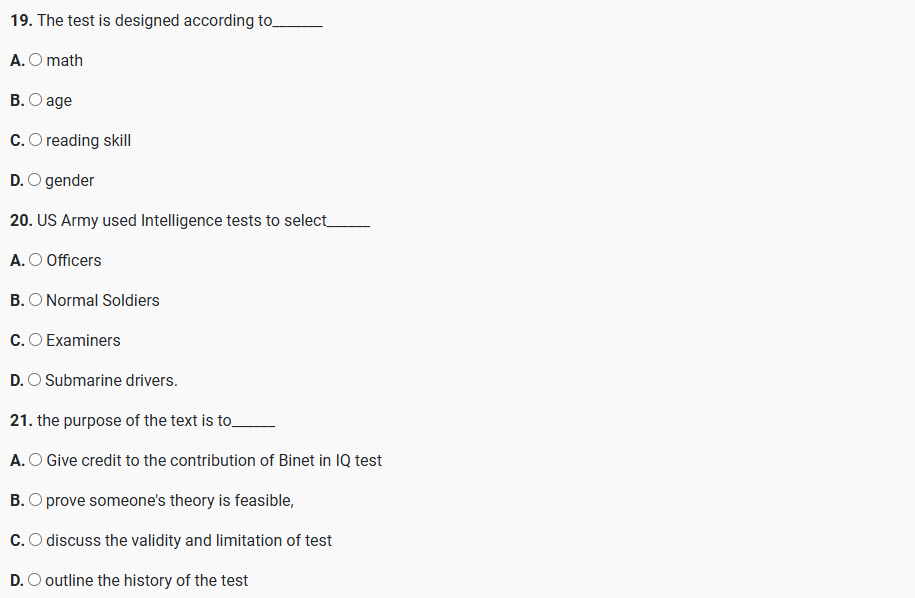

A. Leatherback turtles follow the general sea turtle body plan of having a large, flattened, round body with two pairs of very large flippers and a short tail. Like other sea turtles, the leatherback’s flattened forelimbs are adapted for swimming in the open ocean. Claws are absent from both pairs of flippers. The Leatherback’s flippers arc the largest in proportion to its body among extant sea turtles. Leatherback’s front flippers can grow up to 2.7 meters (9 ft) in large specimens, the largest flippers (even in comparison to its body) of any sea turtle. As the last surviving member of its family, the leatherback turtle has several distinguishing characteristics that differentiate it from other sea turtles. Its most notable feature is that it lacks Q8 the bony carapace of the other extant sea turtles.

B. During the past month, four turtles have washed up along Irish coasts from Wexford to Kerry. These turtles are more typical of warmer waters and only occur in Irish waters when they stray off course. It is likely that they may have originated from Q10 Florida, America. Two specimens have been taken to Coastal and Marine Resources Centre (stored at the National Maritime College), University College Cork, where a necropsy (post mortem for animals) will be conducted to establish their age, sex and their exact origin. Q1 During this same period, two leatherback turtles were found in Scotland, and a rare Kemp’s Ridley turtle was found in Wales, thus making it an exceptional month for stranded turtles in Ireland and the UK.

C. Actually, There has been extensive research conducted regarding the sea turtles’ abilities to return to their nesting regions and sometimes exact locations from hundreds of miles away. In the water, their path is greatly affected by powerful currents. Q2 Despite their limited vision, and lack of landmarks in the open water, turtles are able to retrace their migratory paths. Some explanations of this phenomenon have found that sea turtles can detect the angle and intensity of the earth’s Q11 magnetic fields.

D. However, Loggerhead turtles are not normally found in Irish waters, because water Q9 temperature here are far too cold for their survival. Instead, adult loggerheads prefer the warmers waters of the Mediterranean, the Caribbean, and North America’s east coast. The four turtles that were found have probably originated from the North American population of loggerheads. However, it will require genetic analysis to confirm this assumption. Q3 It is thought that after leaving their nesting beach as hatchlings (when they measure 4.5 cm in length), these tiny turtles enter the North Atlantic Gyre (a giant circular ocean current) that takes them from America, across to Europe (Azores area), down towards North Africa, before being transported back again to America via a different current. This remarkable round trip may take many years during which these tiny turtles grow by several centimetres a year. Loggerheads may circulate around the North Atlantic several times before they settle in the coastal waters of Florida or the Caribbean.

E. Q4 These four turtles were probably on their way around the Atlantic when they strayed a bit too far north from the Gulf Stream. Once they did, their fate was sealed, as the cooler waters of the North East Atlantic are too cold for loggerheads (unlike leatherback turtles which have many anatomical and physiological adaptations to enable them to swim in our seas). Once in cool waters, the body of a loggerhead begins to shut down as they get ‘cold stunned’, then get hypothermia and die.

F. Leatherbacks are in immanent danger of extinction. A critical factor (among others) is the harvesting of eggs from nests. Valued as a food delicacy, Leatherback eggs are falsely touted to have aphrodisiacal properties in some cultures. The leatherback, unlike the Green Sea turtle, is not often killed for Q12 its meat; however, the increase in human populations coupled with the growing black market trade has escalated their egg depletion. Q5 Other critical factors causing the leatherbacks’ decline are pollution such as plastics (leatherbacks eat this debris thinking it is jellyfish; fishing practices such as longline fishing and gill nets, and development on habitat areas. Scientists have estimated that there are only about Q7 35,000 Leatherback turtles in the world.

G. We are often unable to understand the critical impact a species has on the environment—that is, until that species becomes extinct. Even if we do not know the role a creature plays in the health of the environment, past lessons have taught US enough to know that every animal and plant is one important link in the integral chain of nature. Q6 Some scientists now speculate that the Leatherback may play an important role in the recovery of diminishing fish populations. Since the Leatherback consumes its weight in jellyfish per day, it helps to keep Jellyfish populations in check. Jellyfish consume large quantities of fish larvae. The rapid decline in Leatherback populations over the last 50 years has been accompanied by a significant increase in Q13 jellyfish and a marked decrease in fish in our oceans. Saving sea turtles is an International endeavor.

Prepare for IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009