IELTS READING HIGH SPEED, HIGH RISE reading practice test has 10 questions belongs to Engineering & Architecture subject..

A Chinese entrepreneur has figured out a way to manufacture 30-story, earthquake-proof skyscrapers that snap together in just 15 days.

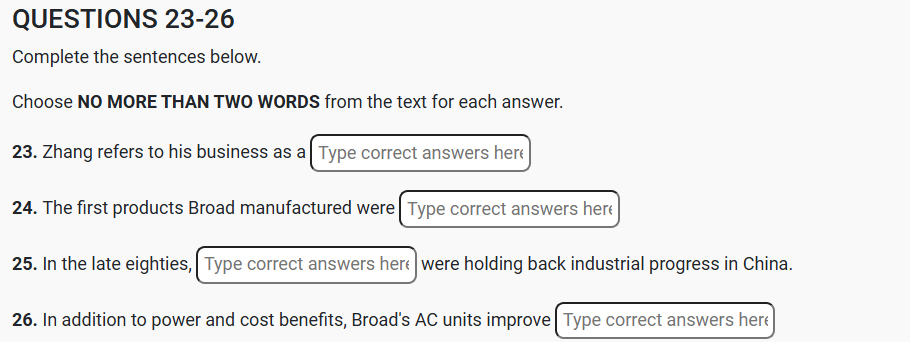

A. Zhang Yue is founder and chairman of Broad Sustainable Building (otherwise known as ‘Broad’) who, on 1 January, 2012, released a time-lapse video of its 30-story achievement. Q14 It shows construction workers buzzing around like gnats while a clock in the corner of the screen marks the time. In just 360 hours, a 100-metre-tall tower called the T30 rises from an empty site to overlook Hunan’s Xiang River. At the end of the video, the camera spirals around the building overhead as the Broad logo appears on the screen: a lowercase that wraps around itself in an imitation of the @ symbol. The company is in the process of franchising its technology to partners in India, Brazil, and Russia. What it is selling is the world’s first standardized skyscraper and with it, Zhang aims to turn Broad into the McDonald’s of the sustainable building industry. When asked why he decided to start a construction company, Zhang replies, ‘It’s not a construction company. It’s a Q23 structural revolution.

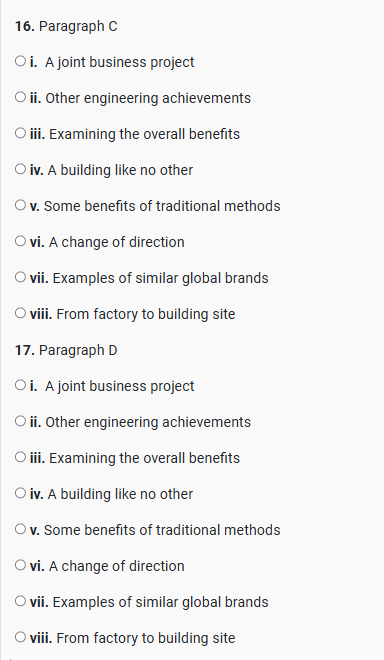

B. So far, Broad has built 16 structures in China, plus another in Cancun. They are fabricated at two factories in Hunan, roughly an hour’s drive from Broad Town, the sprawling headquarters. The floors and ceilings of the skyscrapers are built in sections, each measuring 15.6 by 3.9 meters with a depth of 45 centimeters. Pipes and ducts for electricity, water and waste are threaded through each floor module while it is still in the Q19 factory. The client’s choice of Q20 flooring is also pre-installed on top. Standardized truckloads carry two modules each to the site with the necessary columns, bolts and tools to connect them stacked on top of each other. Once they arrive at the location, each section is lifted by crane directly to the top of the Q15 building, which is assembled like toy Lego bricks. Workers use the materials on the module to quickly connect the pipes and wires. The unique Q21 column design has diagonal bracing at each end and tabs that bolt into the floors above and below. In the final step, heavily insulated exterior walls and windows are slotted in by crane. The result is far from pretty but the method is surprisingly safe – and phenomenally fast.

C. Zhang attributes his success to his creativity and to his outsider perspective on technology. He started out as an art student in the 1980s, but in 1988, Zhang left the art world to found Broad. The company started out as a maker of non-pressurized Q24 boilers. His senior vice-president, Juliet Jiang, says, ‘He made his fortune on boilers. He could have kept doing this business, but … Q16 he saw the need for nonelectric air-conditioning.’ Towards the end of the decade, China’s economy was expanding past the capacity of the nation’s electricity grid, she explains. Q25 power shortages were becoming a serious obstacle to growth. Large air-conditioning (AC) units fueled by natural gas could help companies ease their electricity load, reduce overheads, and enjoy more reliable Q26 climate control into the bargain. Today, Broad has units operating in more than 70 countries, in some of the largest buildings and airports on the planet.

D. For two decades, Zhang’s AC business boomed. But a couple of events conspired to change his course. The first was that Zhang became an environmentalist. The second was the earthquake that hit China’s Sichuan Province in 2008, causing the collapse of poorly constructed buildings. Initially, he says, he tried to convince developers to refit existing buildings to make them both more stable and more sustainable, but he had little success. So Zhang drafted his own engineers and started researching how to build cheap, environmentally friendly structures that could also withstand an earthquake. Within six months of starting his research, Zhang had given up on traditional methods. He was frustrated by the cost of hiring designers and specialists for each new structure. The best way to cut costs, he decided, was to take building to the factory. But to create a factory-built skyscraper, Broad had to abandon the principles by which skyscrapers are typically designed. Q17 The whole load-bearing structure had to be different. To reduce the overall weight of the building, it used less Q22 concrete in the floors; that in turn enabled it to cut down on structural steel.

E. Around the world, prefabricated and modular buildings are gaining in popularity. But modular and prefabricated buildings elsewhere are, for the most part, low- rise. Broad is alone in applying these methods to skyscrapers. For Zhang, the environmental savings alone justify the effort. Q18 According to Broad’s numbers, a traditional high-rise will produce about 3,000 tons of construction waste, while a Broad building will produce only 25 tons. Traditional buildings also require 5,000 tons of water onsite to build, while Broad buildings use none. The building process is also less dangerous. Elevator systems – the base, rails, and machine room – can be installed at the factory, eliminating the risk of injury. And instead of shipping an elevator car to the site in pieces, Broad orders a finished car and drops it into the shaft by crane. In the future, elevator manufacturers are hoping to preinstall the doors, completely eliminating any chance that a worker might fall. ‘Traditional construction is chaotic,’ he says. ‘We took construction and moved it into the factory.’ According to Zhang, his buildings will help solve the many problems of the construction industry and what’s more, they will be quicker and cheaper to build.

Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009