| IELTS Reading WHEN EVOLUTION WORKS AGAINST US reading practice test has 10 questions belongs to Biology & Evolution subject.. |

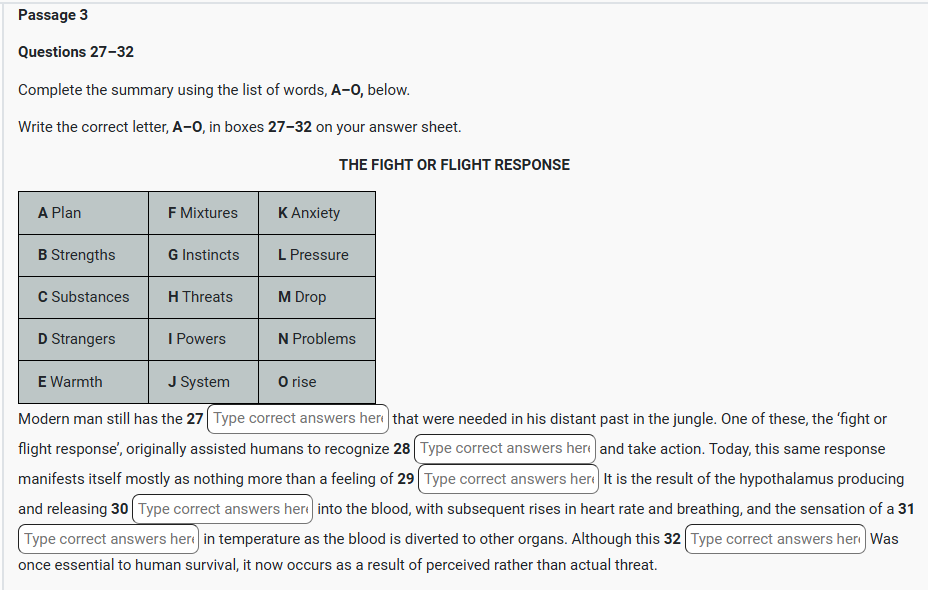

Life has changed in just about every way since small tribes of hunter-gatherers roamed the earth armed with nothing but spears and stone tools. We now buy our meat from the supermarket rather than stalking it through the jungle; houses and high-rises shelter us at night instead of caves. But despite these changes, some very basic responses linger on. The short, Q29 sharp feeling of heightened awareness that sweeps through us when a stranger passes in a dark alley is no different, physiologically speaking, from the sensation our ancestors experienced when they were walking through the bushes and heard a dry twig snap nearby. It’s called the ‘fight or flight’ response, and it helps us to identify dangerous situations and act decisively by, as the name suggests, mustering our strength for a confrontation or running away as fast we can.

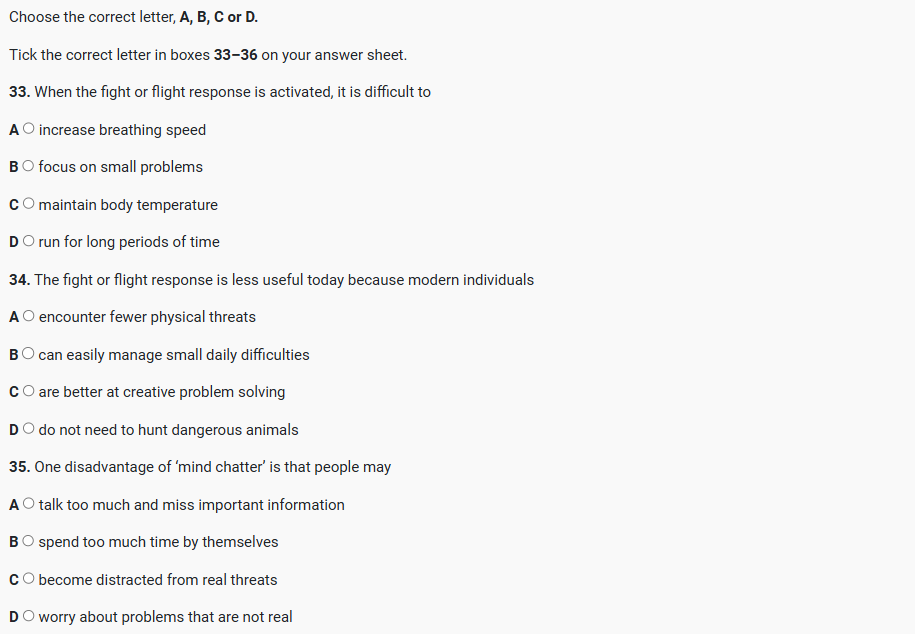

This shift to survival mode is often popularly described as a sudden unease, a sense that a situation is ‘off’ or ‘not right’. However, the sense is actually the outcome of an incredibly complex mind-body process which involves the brain’s ‘fear centre’, Q30 the hypothalamus, advising the sympathetic nervous Q32 system and the adrenal-cortical system to work, at first separately, and then together, to blend a potent mix of hormones and chemicals and secrete them into the bloodstream. Our heartbeat rises, along with our respiratory rate. Skin feels cold (hence the ‘shiver’ down the spine) as blood supply is redirected to the larger muscles required for a physical confrontation or a hasty retreat. The ability to concentrate on issues of minor importance also suffers, as the brain tends to prioritise ‘big picture’ thinking at this time.

Without this Q27 instinctive response, the human race would never have survived, but at present it is often more of a hindrance than a help. Although instances of physical Q28 threats have decreased over the years, activation of the fight or flight response has actually increased, largely in response to mental frustrations. This poses a problem, however, because the fight or flight mechanism functions most helpfully as a response to something that can cause bodily harm, such as a falling tree or a wild animal, rather than in response to a fulminating boss, a traffic jam, or a spouse who has not returned a phone call. During these instances of mental distress, the physical manifestations of fight or flight, such as an inability to think rationally and calmly, can actually exacerbate the problem. A similar case of an evolutionary development overstaying its welcome is the example of ‘mind chatter’. Mind chatter is the ceaseless train of scattered thoughts and self-talk that occupies our mind, ensuring we are always ‘switched on’, searching for danger and threats. This would have been a boon for a solitary caveman on a three-hour hunting expedition, but in a modern world already overloaded with sensory input, it causes us to fret about non-existent predicaments and occasionally needlessly triggers the fight or flight response.

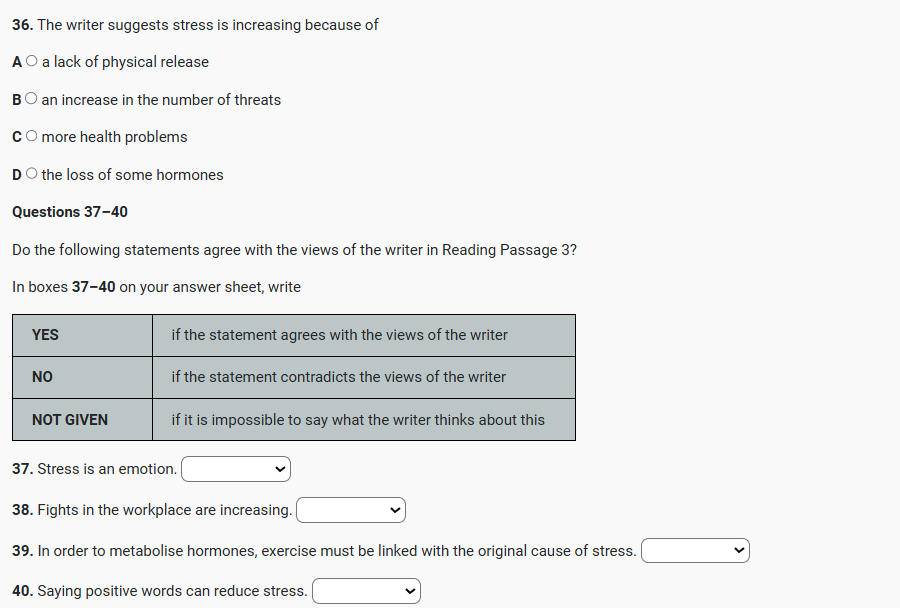

These twin forces, mind chatter, and the fight or flight response, have combined to wreak havoc on the modern psyche and have led to a spike in what Q37 some studies have suggested is a cause of up to eighty percent of all illness today: stress. Stress, erroneously considered by many to be a mere feeling, is actually a physiological condition resulting from a cumulative accrual of certain hormones in the body, hormones that can help us in quick, sharp doses, but which are toxic if they are not properly metabolised. Q39 Metabolism of these potentially toxic hormones relies on physical exertion, which originally evolved as part of the fight or flight process – hormone release was usually followed by physical exertion (fighting or running), which returned the body to a state of balance. In present day encounters, however, the vital element of physical exertion is missing: a resentful employee cannot punch his co-worker, for example, and a frustrated driver is unable to simply ram his way through a packed intersection.

What can be done to restore the balance? Stress researcher Neil F. Neimarck, perhaps not surprisingly, recommends physical exercise as one useful strategy. Fortunately, the brain is not clever enough to realise that this exercise is completely unrelated to the original stress stimulus, and in this way we can effectively ‘fool’ our bodies into metabolising stress hormones by punching a boxing bag instead of the person who annoyed us in the first place. Another option is the ‘relaxation response’, discovered by Harvard cardiologist Herbert Benson. Benson found that certain behaviours, such as deep breathing, meditation, and the repetition of simple, affirmative phrases, acted as an antidote to mind chatter and the fight or flight responses, calming the nervous system and inducing a relaxed state of mind and body instead. Integrating these methods into our lives will be important if the cycle of stress accumulation that is so endemic in modern.

Western society is to be stopped.

Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional.

![]()

8439000086

8439000087

7055710003

7055710004

IELTS Simulation 323 GMS Road, Near Ballupur Chowk, Dehradun, India

![]()

email: info at ieltsband7.com

Boost Your Score: Practice IELTS Online with IELTS Simulator Prepare for IELTS Effectively Using IELTS Simulator Ace the IELTS: Try Realistic Practice on IELTS Simulator IELTS Simulator: Online Practice to Improve Your IELTS Score Rocky Bay field trip listening practice test has 10 questions belongs to the Leisure & Entertainment subject. Prepare for IELTS IELTS Test International Experienced Teacher Best Training By CELTA Trainer. Best Results Easily Get Required Score IELTS Exam Dates Available, Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, Professional. Easily Get Required Score I am interested in IELTS Pass with Confidence, Dehradun Small Batch Size with Flexible Time, professional faculty. Learn From Experienced Teacher Best IELTS Coaching Dehradun Best IELTS in Dehradun Uttarakhand GMS Road BEST coaching in Dehradun Apply for Class Courses Today Good Results. Small Batch Size, Flexible Time and Professional IELTS Teacher Best IELTS coaching classes IDP certified British Council trained and CELTA certified experienced trainer. Easily Get Required Score Tel:8439000086 Tel:8439000087 Tel:7055710003 Tel:7055710004 Tel:7055710009